The "Old Deluder Law" Revisited

[Trivia: who were the three most famous Americans killed on March 6, 1836?]

In the 1640’s, the then-colony of Massachusetts pioneered the way for government-funded, compulsory education in America. The 1647 law itself is striking to read:

It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures, as in former times keeping them in an unknown tongue, so in these later times by perswading from the use of tongues, that so at least the true sense and meaning of the Originall might be clowded by false glosses of Saint-seeming deceivers; and that Learning may not be buried in the graves of our fore-fathers in Church and Commonwealth, the Lord assisting our indeavors: it is therefore ordered by this Court and Authoritie therof;

That every Township in this Jurisdiction, after the Lord hath increased them to the number of fifty Housholders, shall then forthwith appoint one within their town to teach all such children as shall resort to him to write and read

This law crops up from time to time in public discourse; National Review’s Kevin Williamson used it as Square One last April to argue with the New York Time’s Frank Bruni on education:

“The schools . . . exist for all of us,” Bruni writes, “to reflect and inculcate democratic values and ecumenical virtues that have nothing to do with any one parent’s ideology, religion or lack thereof.”

This is naïve and ahistorical.

The first public-school law in Massachusetts — the first in what would eventually be these United States — bears the wonderful name the “Old Deluder Satan Act” of 1647. Like every public-education law that ever has existed or ever will exist, it was meant to serve a particular parochial agenda. In this case, the law was intended to encourage literacy in order that young Christians might study Scripture and thereby fortify their souls against the seductions of the Catholic Church. Of course, there was no Catholic Church in Massachusetts at the time, and Boston would not see its first public Mass celebrated for another century and a half. In the same year as the education law was passed, Massachusetts banned Jesuit priests from entering the colony — on penalty of death.

Williamson’s point is that you cannot have a system of compulsory and government-funded schooling without a set of common values it is aiming at, and I agree that naïveté undergirds most popular belief that that’s wrong. And of course, what exactly those boundaries are has long been a heated point of discussion; a 2005 article from the History of Education Quarterly revisits those same Catholic concerns:

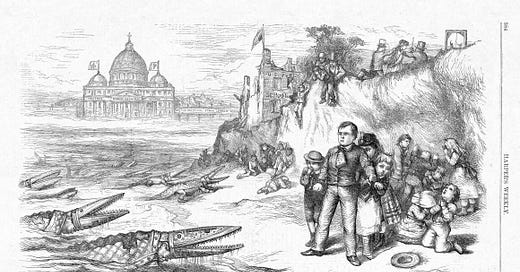

In the decade and a half after the Civil War, the American public school rose and fell as a central issue in national and state politics. After a relative calm on matters of education during and immediately after the War, the Republican Party and Catholic Church leaders in the late 1860s and early 1870s joined a bitter battle of words over the future of public education who should control it, how should it be financed, and what should it teach about religion. These battles often reflected very different world views. Leading Protestant ministers and Republican politicians waved the threat of a rising antidemocratic "Catholic menace" as the new bloody shirt and championed their own educational ideal as a remedy-religiously neutral, ethnically and racially inclusive common schools. While Democrats tended to downplay school issues, Catholic Church leaders countered with their own screed: common schools were hardly common, embodying either inherently Protestant notions of religion or the atheism of no true religious creed at all. New York City became the epicenter of these cataclysmic debates, and the brilliant cartoonist Thomas Nast immortalized the Radical Republican side of the issue in the pages of Harper's Weekly.

Thomas Nast’s work included cartoons like below, where the bishops are crocodiles and the Democratic politicians are shepherding children down to the riverside.

But that initial “Old Deluder” law—that law has long been recognized as a significant piece of legislation. The definitive post-Federalist-Papers-but-pre-Civil-War discussion of US laws was Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story’s Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (1833), which discusses the laws of the colonies in turn. Of Massachusetts, Story wrote:

But the most striking as well as the most important part of their legislation is in respect to education. As early as 1647, the General Court, “to the end,” as the preamble of the act declares, “that learning may not be buried in the graves of our forefathers in church and commonwealth,” provided, under a penalty, that every township of fifty householders “shall appoint a public school for the instruction of children in writing and reading, and that every town of one hundred householders “shall set up a grammar school, the master thereof being able to instruct youth so far as may be fitted for the university.” This law has, in substance, continued down to the present times; and it has contributed more than any other circumstance to give that peculiar character to the inhabitants and institutions of Massachusetts, for which she, in common with the other New England states, indulges an honest, and not unreasonable pride.

(Emphasis mine.)

It feels weird to peel back what Massachusetts must have looked like, before its era as a bastion of Liberalism and, before that, a home of urban Catholic and Irish life. For that matter, a cornerstone of American law and culture like this, long recognized as such, should be more front-and-center as a part of our debates and our understanding of the role of education. It reminds me of that line, often attributed to G.K. Chesterton though I failed to find any source for it,

There are two kinds of people in the world, the conscious dogmatists and the unconscious dogmatists. I have always found myself that the unconscious dogmatists were by far the most dogmatic.

If our education is to dogmatically teach values, let us at least have the candid discussion of what those values are to be—rather than deny the inculcation of values only to have them surface at the unvetted discretion of administrators and other, well, government employees.

~

Answer: When Santa Anna’s forces took the Alamo, they killed Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie, and commander William Travis.