The Lawlessness of the Pro-Abortion Judges

[Trivia: How many of EM Forster’s 6 novels can you name?]

How blatantly is a judge allowed to invent a ruling?

One of the downstream developments since the US Supreme Court (finally) overturned Roe v. Wade last summer is that judges in lower courts have been striking down state laws that prohibit abortion in the name of some right or other.

I noted this last August happening in Kansas. The Kansas Constitution’s Bill of Rights includes the line, “Equal rights. All men are possessed of equal and inalienable natural rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

That line is the fullest extent of the grounding taken by the Kansas Supreme Court some 4 years ago to strike down abortion laws and tie the hands of the legislature on this subject (abortion is only prohibited after week 22). Their opinion doing so begins,

Section 1 of the Kansas Constitution Bill of Rights provides: "All men are possessed of equal and inalienable natural rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." We are now asked: Is this declaration of rights more than an idealized aspiration? And, if so, do the substantive rights include a woman's right to make decisions about her body, including the decision whether to continue her pregnancy? We answer these questions, "Yes."

This is willful ideology at work in the most inexcusable way. Everything about this “reasoning” is wrong. It posits a false dichotomy (viz. between an idealized aspiration and additional but unarticulated substantive rights), completely misstates the question at hand, shoehorns in a particular policy preference with nothing more than an arbitrary “Yes,” is intentionally blind to the crux of the entire question—that it is not the woman’s body in question—and, ultimately, relies on a guarantee of the inalienable natural right of life to permit the legalized killing of the innocent. It is maximally perverse.

It is emphatically not the province of the judicial department to assert broad aims of government and use that as an excuse to give life to policies they favor. This isn’t particularly new, even if it is particularly heinous in this particular application. An equivalently logical instance was cited by the late, great Justice Antonin Scalia in his manual on the application of originalism, Reading Law:

In Hill v. Conway, the Vermont Supreme Court confronted a provision of state law dealing with the suspension of drivers’ licenses. The provision said that “the suspension period for a conviction for first offense . . . of this title shall be 30 days; for a second conviction 90 days and for a third or subsequent six months, . . . but if a fatality occurs, the suspension shall be for a period of one year.” The Commissioner of Motor Vehicles suspended Randall Hill’s driver’s license for “365 days following his first offense conviction on a charge of careless and negligent operation with death resulting.” Hill contended that because the 30-day punishment for a first offense is set apart from the one-year fatality provision by a semicolon, 30 days should have been the limit of his suspension.

The Vermont court held that the semicolon should not prevail. The punctuation of a statute, it said, will not be more important to interpretation than the legislative intent. (See § 67.) Leaping to the most general description of legislative purpose, the court said that the statute was meant to preserve public safety and remove irresponsible drivers from the road. To bar the state from suspending for more than 30 days the license of a driver whose first offense resulted in a death would be “an absurd and irrational result, and inconsistent with the legislative objective as we construe it to be.” In short, the court abused the absurdity doctrine (see § 37) and disregarded the rule of lenity (see § 49). Such are the slighting indignities to which semicolons are often subjected.

(Emphasis added.)

South Carolina’s high court’s much more recent action to guarantee abortion makes some more effort than Kansas’ does—though with no more legal merit to their arguments. They hang their hat on the following text, and explain it thus:

Unlike the United States Constitution and the constitutions of most of our sister states, South Carolina's Constitution includes a specific reference to a citizen's right to privacy. That provision states: "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures and unreasonable invasions of privacy shall not be violated . . . ." S.C. Const., art I, § 10. In this case, we are asked to determine whether that right to privacy extends to a woman's decision to have an abortion, and, if so, whether the Act unconstitutionally infringes upon that right. We are not asked to determine whether our constitution mentions the word "abortion"—clearly it does not. Instead, the fundamental question before the Court is whether this Act, which severely restricts and, in many cases, prohibits a woman's decision to terminate a pregnancy, constitutes an "unreasonable invasion of privacy."

Their argument is essentially that a right of privacy, recognized by their state constitution, existed prior to the constitution, and that that included abortion. In their own words, “In analyzing the import of the words of the amendment, it is important to note that this right to privacy was not created out of whole cloth in 1971, but instead was recognized as having always existed.” Why in the world such a privacy right would encompass abortion is a mystery, one for whose resolution they depend on the ever-straying course of SCOTUS precedent.

And here, by the way, I must mention the way that their recounting of this history includes the following note:

Fast on the heels of Griswold, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to privacy, emanating from the Bill of Rights and applying to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, protected a woman's decision to terminate pregnancy in the first trimester without interference from the state. Roe v. Wade.

(Emphasis mine.)

They’re careful to distinguish the fact that the Roe overturning relied partially on the complete absence of privacy language in the US Constitution, and therefore it “does not control.” Never mind that they would like the entire lineage of avowedly flawed cases connected with Roe to control, in spite of the fact that those cases only had impact because they were issued by the US Supreme Court, on the allegation that they were interpreting the national constitution—which they weren’t, as the Court has by now partially acknowledged. Heck, the entire “always-having-existed privacy right” enshrined by the South Carolina Constitution in 1971—was enshrined prior to Roe, when abortion was illegal in South Carolina.

As a dissenter to that opinion noted,

Abortion is not "deeply rooted" in our state's history . . . To the contrary, it is the regulation and restriction of abortion that is deeply rooted in our state's history. Even during the past fifty years, under Roe and Casey, many state legislatures throughout the nation enacted laws placing limits and restriction on abortions.

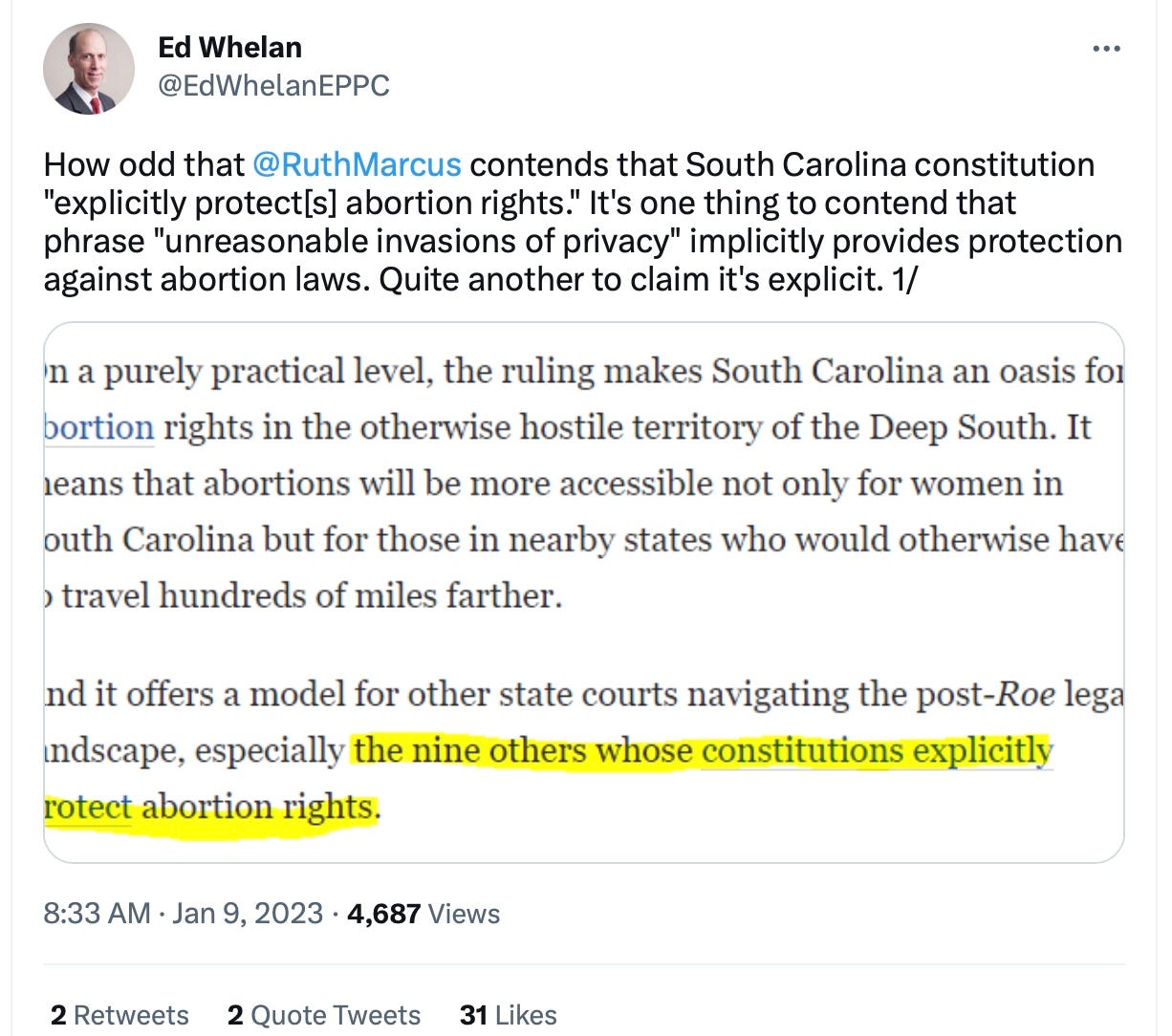

Shortly after this opinion, Ed Whelan of the Ethics and Public Policy Center noted that a WaPo journalist was so out of line as to content that South Carolina’s Constitution was “explicit” in its protection of these rights.

Kansas, South Carolina—Wisconsin threatens to be next. A swing seat on the state Supreme Court is up for grabs in an upcoming election, and the great state’s on-the-books-since-1849-i.e.-the-year-after-statehood abortion ban is right in the crosshairs of the liberal activists running to take power from the bench and implement an agenda they’re promising to voters. One front-runners (obnoxiously inescapable) ads include the campaign promise,

“On the Supreme Court, I’ll be a common-sense judge . . . I believe in a woman’s freedom to make her own decision on abortion.”

(Once again I find myself thinking of projection. Is the Left perennially incensed at conservative beliefs, even personal ones, because they comprehend no distinction between a personal belief and what one is bound to enact when giving power? Or is this just another case of branding trying to be as effective as possible, and I’m over-reading everything? For once, I actually do suspect it’s the former.)

I don’t know what part of the Wisconsin Constitution would be cited to overturn Wisconsin’s abortion law. Probably these same judges haven’t thought it through themselves; after all, if the result is predestined to bear a nonexistent relationship with the underlying text, it’s not like it much matters what the text is.

Of course, opening up the Constitution, I see that the opening lines pretty much doom the abortion ban in this state:

All people are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights; among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

That’s almost exactly the same language leveraged to that purpose in Kansas.

I don’t know what the solution is to power grabs this naked and unjustifiable. I understand that on an electoral level, people are going to vote with this policy result in mind without any thought about the underlying legal justification for the promised bread and circuses. (I wish the stakes were as harmless as bread and circuses.) I suppose that public pro-abortion intellectuals prevent themselves from coming across like pure Machiavels (which would tacitly give their opponents license to be the same) by voicing white-hot moral furor as their justification, as well as by offering arguments, face-saving even if structurally unsound. (And the further downstream from the authorities, the more cavalier people are in their claims—the South Carolina court’s decision is at pains to seem like a reasonable interpretation of a law, while the WaPo journalist just lies and calls it “explicitly protect[ed].”

~

Answer: Where Angels Fear to Tread, The Longest Journey, A Room with a View, Howards End, A Passage to India, and (posthumously published) Maurice.