[Trivia: Mikhail Gorbachev passed away this week, and I have to admit I’m persuaded by conservative commentator Ben Shapiro’s argument that he’s being widely feted in spite of being an unrepentant Marxist-Leninist in a subtle attempt by the West’s intelligentsia to avoid paying due tribute to the real heroes of the Cold War—Reagan, PM Margaret Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II. Nevertheless, commemorating his passing, what do all of the following have in common? Mikhail Gorbachev, William F. Buckley, Eleanor Roosevelt, Sean Connery, Sir Christopher Lee, Jack Lemmon, Melissa Joan Hart, Ben Kingsley, Dom DeLuise, Antonio Banderas, Sir John Gielgud, Patrick Stewart, Kirstie Alley, Boris Karloff, Viola Davis, Captain Kangaroo, David Tennant, David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Sting, Basil Rathbone, and Weird Al Yankovic?]

There’s a hundred little topics I’d like to write about on this “Bookshelf”—Shakespeare, Scorsese, Philemon, “common knowledge”—but I wanted to just say a few things about Sonic the Hedgehog.

I guess this train of thought started a couple days ago when I came across the Medium blog of an old, musically-oriented high school friend of mine who was reviewing old soundtracks and commented on the Sonic franchise, which we’d been fans of together back in the day. Then today, out of the blue, I came across a new episode of a podcast I hadn’t heard of that featured as a guest a video game webcomic artist whose comic and podcast had been a favorite of mine before it concluded, back in 2010. So voicing these thoughts felt right.

But enough quasi-apologizing—my old friend commented that Sonic was at its core a flawed franchise because it was, after all, a product of marketing decisions that had no brilliant gameplay dynamic (like Tetris), no deep gameplay (like many of today’s competitive online games, e.g. League of Legends or Valorant), and no captivating story. All it could give you was the feeling that you were moving fast, nothing more.

So I think, for all of the franchise’s severe and head-scratching mistakes from the past 20 years or so, that this is wrong, and that there’s a fun heart to the series regardless of how many times the creators pass over it in favor of a cheap cash-grab. As G.K. Chesterton might have said, real Sonic gameplay was not developed and found lacking; it was found difficult and left undeveloped.

The Marketing Point

Sonic the Hedgehog was the result of a somewhat-flagging video game company (Sega) that wanted an appealing mascot featured on games you could only play on their consoles (like the 16-bit Sega Genesis), specifically to rival Nintendo’s massively popular Mario. That’s not the most auspicious origin story. Still, I’m reminded of Shakespeare’s plays. I’ve known people, people who’ve acted routinely in his plays, openly mock the idea of considering Shakespeare great literature. “What, Hamlet? You’re discussing that seriously? I wrote that when I was on a massive bender” is the gist of their perspective (and nearly a direct quote). And, yes, Shakespeare was a craftsman whose dinner depended on his outputting a product at an intense clip—he wrote 38 five-act plays over his not terribly long life, much of that content in verse.

But on the other hand, I think of a lecture I heard an English professor deliver once on Hamlet, where he suggested that Shakespeare was not only creative, but the sort of craftsman that we’ve probably met who just couldn’t help himself, going above and beyond what he needed to do to earn his daily bread, compulsively pushing himself to do more fun and interesting things with his product.

I may or may not buy that idea as written about Shakespeare, but if nothing else that serves as an illuminating image to demonstrate that marketing roots are not a kill-shot that a product is inferior.

Especially since that’s also the sort of thing you’d expect from the specific creators of Sonic (foremost the lead of Sonic Team, one Yuji Naka). Those same people were responsible for several other franchises, memorable characters, and world-building—the 90’s in particular saw a real flourishing of activity, when they were consistently crafting distinct characters to showcase highly specific game dynamics developed into full games. Examples include Nights into Dreams on the Sega Saturn, the Carl Jung-inspired result from Yuji Naka wondering what it would be like to fly; ChuChu Rocket! on the Sega Dreamcast, a grid-based puzzle game realized as an effort to guide space mice safely to rockets whilst avoiding space cats; Crazy Taxi, a fast-paced driving game where you find and transport passengers around an intensely vertical beach metropolis (San Francisco?); the list goes on.

The Mario Parallel

But keeping going with Mario, I think it’s illuminating to see where the two were similar and where they diverged. After all, Mario’s original name wasn’t Mario—it was “Jumpman.”

Playing Mario games when they first debuted, you were struck by the flea-like nature of the character, and how high (especially compared to his size) he could shoot up into the air. These days, that’s not really a trademark feature of his platformers; if anything, what’s striking is going back and playing 80’s-era platformers and realizing how grounded most other characters are.

Mario gameplay had a distinguishing dynamic that worked, that set them apart and that worked in concert with everything else going on in those platforming games.

But they didn’t just make Mario jump higher and higher.

That might have been an interesting series of games. But I have every confidence that it wouldn’t have matured into the colossal global standard for both 2D- and 3D-platforming that it’s become. Instead, they went in a more sober direction. They went selected the aspects of his platforming that worked and that had potential to grow and went with them. They introduced twists on the gameplay to modestly expand it, often working (Super Mario Bros. 3’s Tanooki suit, Super Mario Galaxy’s tiny and circumambulable planets) and only sometimes earning criticism as outright gimmicks (the FLUDD contraption in Super Mario Sunshine). They went so far as to erase his on-the-nose name and give him a more human one—but one that still had character.

The problem with Sonic is that the team couldn’t, or didn’t, grow. The distinguishing feature (speed) remained focal even when the novelty had long worn off—gameplay from one game to the next consisted, for a long time, of a speed arms race between Sonic and itself. And when that failed, they jumped the shark with gimmicks—surfboard racing, guns, cars, team gameplay, casting Sonic in the world of King Arthur or the Arabian nights, a homegrown werewolf. (I have a hard time believing all of those are real even as I write them.)

And I say that that’s the problem with Sonic because, at the heart of everything, is, in fact, a solid core for a video game franchise and series. Gameplay dynamic? Sonic is a platformer in the key of pinball. The original Genesis games modified familiar running and jumping to include physics in a meaningful and interesting way. Deep gameplay? This is Sega’s hallmark. They are, at heart, an arcade game company that by nature crafts a gameplay dynamic into an experience that can be refined, optimized, and become-expert-at. The original games understood this, which is why they had branching paths, rewarding both course memorization and fast-twitch speediness as well as exploration and treasure hunting. Compelling story? Sonic has, from the beginning, featured enemies that are robotic contraptions designed to cause damage and chaos—and, when busted, little critters famously fly out of them.

Before: evil imitation crab. (Although as a former Marylander, it’s hard not to always see imitation crab as evil.)

After: an innocent, free birdie

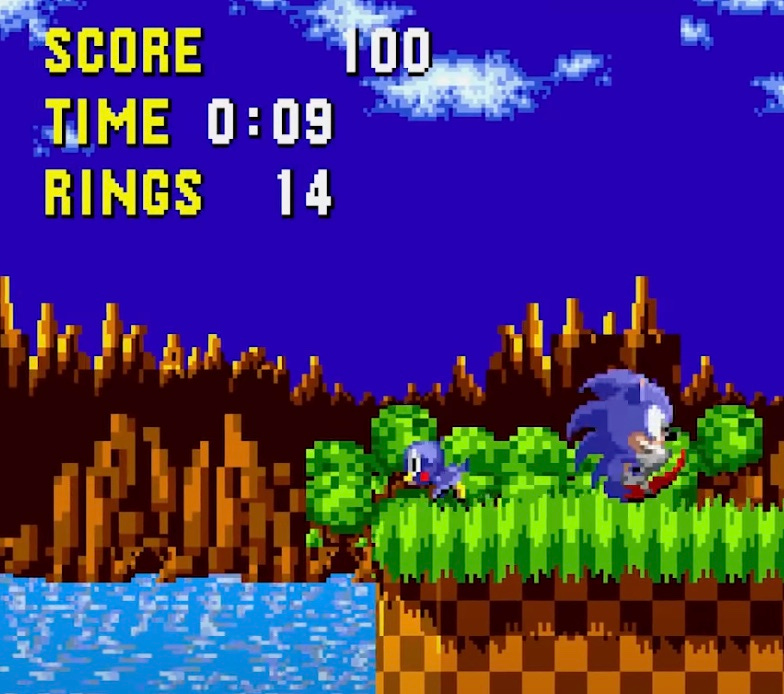

It’s honestly a really subtle, cool, pervasive contest between nature and freedom versus mechanization and control. (Although Sonic’s no Luddite—he famously wears sneakers.) The game itself writes this in majuscule, as the level settings progress from the famous green hill pictured above to a completely mechanic factory/lair.

And, to be fair, cultivating and preserving that probably would have been hard. Crafting levels with multiple branching paths that specifically reward familiarity and expert timing, especially trying to do it all in three dimensions—yeah, that’s hard. And even so, Nintendo has done things the right, hard way, keeping to the straight and narrow, and received criticism over the years for (1) the dearth of main series games (them preferring to release few quality ones rather than many mediocre ones) and (2) being overly formulaic to the point of feeling like we’re still sort of playing the same games (we’re not, of course, it just feels that way at times). But better that than the lambasting that Sonic has received, and earned! The Wikipedia page for “List of video games notable for negative reception” (which I could swear used to be titled, in the days of an earlier Internet, something like “Contenders for worst video game of all time”) has multiple entries from the Sonic series.

I think, with a lot of other people, that Sega really gave it their all so long as they had their own consoles to try to sell. Their last proprietary console, the Dreamcast, featured the Sonic Adventure games, which remain the pinnacle of 3D Sonic: they’re games that struggle with having full-blown cutscenes with voice actors (which Nintendo chose to eschew with Mario) and including some brand new gameplay dynamics (like mech shooting or . . . fishing), but overall those remain special because even when they are being overly experimental or goofy, there is a real sincerity and confident ambition to them. To this day, I think playing Sonic Adventure as a 7-year-old was a formative experience for me because of its out-of-the-box approach to the storytelling. You could progress through the events of the story as six different characters (Sonic, Tails, etc.). But they didn’t just recycle cutscenes every time characters interacted at the same event. Different things got shown happening depending on which character you were playing through. Not in a “choose your own adventure” kind of a way, since canonically one sequence of events transpires and the material outcome in constant, but matter-of-factly the way things happens was incompatibly different. This wasn’t original to Sonic Team of course (almost every comment on this facet I’ve seen has described it specifically as “Rashomon”-like), but that’s such a wildly cool thing to put into a game ostensibly for children. It blew my mind. Years later, when I read Moby Dick, the one part of the book I genuinely enjoyed reading was when the prized doubloon is contemplated by different characters who look at that same piece of gold currency and conceptualize very different things. (Maybe this is a chicken-and-egg thing, where I had a pre-existing propensity to find that sort of thing cool which is what attracted me towards Sonic Adventure to begin with—I can’t be sure—but regardless, it’s a really cool thing about its story.)

At its heart, the Sonic franchise offered the world something special. And that’s before we get into the enchanting use of color design, the truly above-and-beyond work that went into crafting apt and catchy music for the series (here’s a great video explaining and discussing that), the frequently (if inconsistently) ground-breaking animation of the series (see this video essay), the ingeniousness of the character design (this video), and so on. It was never supposed to be about going fast.

~

Answer: All of the above have narrated, in part or in whole, the story of Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. Here are a couple links: Sean Connery, Boris Karloff, David Tennant.