Mondata: Old Testament Quotes for New Testament Folks

[Trivia (inspired by Morning Brew): to date, only 8-ish countries have won the World Cup. How many of them can you name?]

“Paul’s letter to them is the New Testament epistle with the most Old Testament quotations.”

This was the final Jeopardy! clue for last Wednesday’s game, the third in a first-to-three Tournament of Champions. The show ruled the response “Who are the Romans?” incorrect and “Who are the Hebrews?” correct.

Now, I could talk for a while about how this is wrong. We don’t know who wrote the letter to Hebrews. To the extent that people have an opinion, it seems to be that it probably wasn’t Paul, not only because the Hebrews-writer neither begins nor concludes the letter by announcing himself as Paul (which Paul does every time he writes), but because the letter style is really different.

Which, by the way, I didn’t realize just how contested this letter was—by some churches, anyway. Wikipedia mentions how “This stylistic difference has led Martin Luther and Lutheran churches to refer to Hebrews as one of the antilegomena, one of the books whose authenticity and usefulness was questioned. As a result, it is placed with James, Jude, and Revelation, at the end of Luther's canon.” Golly. And to think that the last time I was looking at a Lutheran study Bible, my beef was its inclusion of the deuterocanonical books. But yeah, the Missouri Lutherans’ “Christian Cyclopedia” says, “Throughout the Middle Ages there was no doubt as to the divine character of any book of the NT Luther [sic] again pointed to the distinction between homologoumena [“universally accepted”] and antilegomena [“not universally recognized”] (followed by M. Chemnitz* and M. Flacius*). The later dogmaticians let this distinction recede into the background. Instead of antilegomena they use the term deuterocanonical. Rationalists use the word canon in the sense of list. Lutherans in America followed Luther and held that the distinction between homologoumena and antilegomena must not be suppressed. But caution must be exercised not to exaggerate the distinction.”

Anyway. Christians do recognize Hebrews, but the book itself doesn’t tell us to think it was Paul and the evidence merely weighing in Paul’s favor is . . . poor. Nonetheless, the Jeopardy! clue clearly implies that the people in question were written to, we know for a fact, by Paul. And yet they deemed correct “Who are the Hebrews?”. In spite of the fact that the authorship is deeply in question.

And what’s worse is that the Jeopardy! writers darn well knew that the authorship is in question. I know because they mentioned as much in a clue last year.

READER: You’re using italics a lot.

AUTHOR: . . . wait, do we call it “italics” because of Italy? Like, because that’s how Italians are supposed to speak, all fired up and emotional?

Italic type was first used by Aldus Manutius and his press in Venice in 1500.[8]

Manutius intended his italic type to be used not for emphasis but for the text of small, easily carried editions of popular books (often poetry), replicating the style of handwritten manuscripts of the period. The choice of using italic type, rather than the roman type in general use at the time, was apparently made to suggest informality in editions designed for leisure reading.

AUTHOR: Huh. Anyway.

“Not to be confused with Barabbas, this companion of Paul has sometimes been credited with writing the epistle to the Hebrews.” That was a clue last June. And yet, and yet.

Nor was this an error without practical importance, the way that people got mad about the incorrect ruling to “What is the emanciptation proclamation?” during Kids’ Week almost 10 years ago. That game’s outcome didn’t actually depend on that ruling. But the rightful winner of this game—the contestant who responded “Who are the Romans?” and whose wager would have secured him a win—was absolutely robbed.

But all of this is actually coincidental. Ever since I mentioned that Matthew specifically wrote a gospel with the Jews as his intended audience, I’ve been meaning to verify what I heard in high school, that Matthew’s gospel is the one that most frequently cites the OT—since, after all, his is the audience to whom that would be most meaningful. It’s certainly felt true enough, every time I’ve reread it. But I’d been wanting to get around tallying OT quotes in the gospels and the rest of the NT, and this finally gave me the drive to do so. (There’s some flexibility in how you could tally the number of OT quotes in a given text—I describe my “methodology” at the end of this post.)

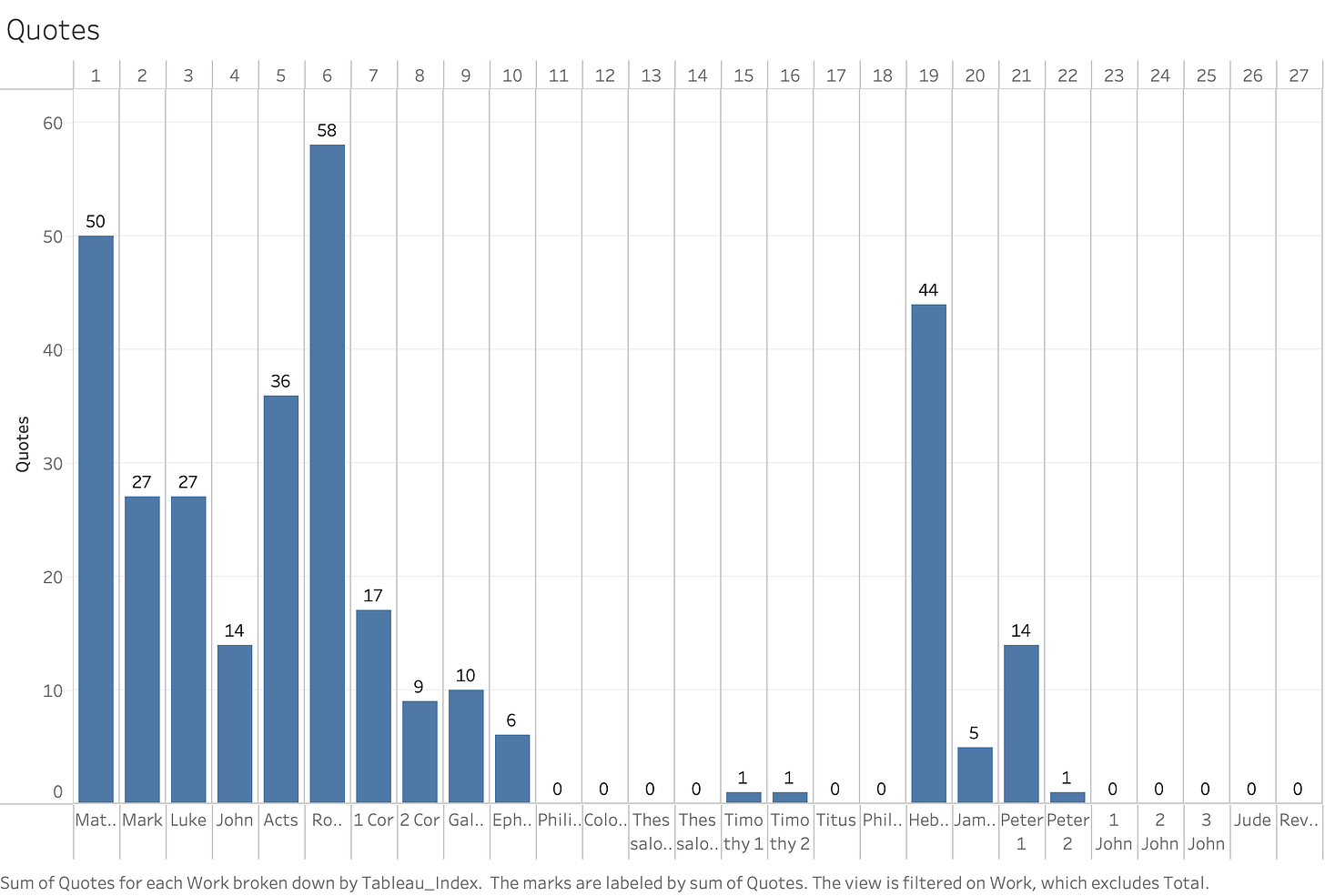

So, how many times do the New Testament books quote the Old Testament?

Matthew and Romans dominate—and oh look, by the way, Hebrews doesn’t even outpace Romans. Hebrews is the wrong response for an entirely different reason.

As one friend of mine says, “What the actual.”

Apparently, this is the norm—as in, I mentioned earlier that I had to make a handful of executive decisions in order to wind up with my Excel spreadsheet that had numbers tallied for each NT book’s quotations. I’m satisfied with my decisions, but reasonable people could have made other ones. And as one redditor noted,

By one source I found, the scoreboard reads Romans 58, Hebrews 42.

. . .

By another source, it was Romans 74, Hebrews 86.

And so it goes - conflicting sources depending on whether you are talking OT reference, OT direct quote, OT paraphrase, et al.

(aside - I must have found 10-12 articles on NT quote counts of the OT, no two had the same count bc it's difficult to delineate an exact quote from a reference/paraphrase.)

So, there are actually some different ways to count this. And Hebrews is consistently silver. Honestly, this is unbelievable.

Anyway, here are the same bars, except ordered by quote volume.

My received intel, by the way, was correct! Matthew has the most. Though wait, isn’t Matthew also real long? (Yes it is. The longest single book in the NT, in fact.)

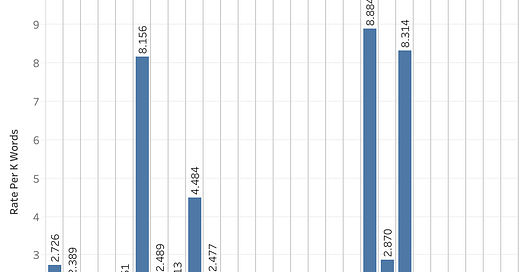

So I calculated rates. Specifically, I wanted to see how frequently a book will include a quote from the OT per 1,000 words of their book. This is what we get, ordered by the canonical order.

I really love this graph. It’s just saying so many things.

Matthew is still the densest gospel (as I’d hypothesized)—although not by a lot! It’s also visible how its volume of quotes really is owed to its length. For that matter, I hadn’t realized that John was relatively so minimal. Romans, Hebrews, and 1 Peter really are leaps ahead of the rest. And also, Revelation doesn’t have a single OT quote! That came as a surprise to me, even though I knew it was a book of prophecy (and even though I was just finishing rereading it as I did this project, haha). I guess that that makes sense, since it’s its own prophecy, but like I said, still surprising.

Aside about Revelation: Note that Jeopardy! is famously scrupulous about ruling “What is Revelations?” incorrect. The title of the book is singular. Although on the other hand, if their clue includes a hint about the title needing to be singular, it’s guaranteed to be this response.

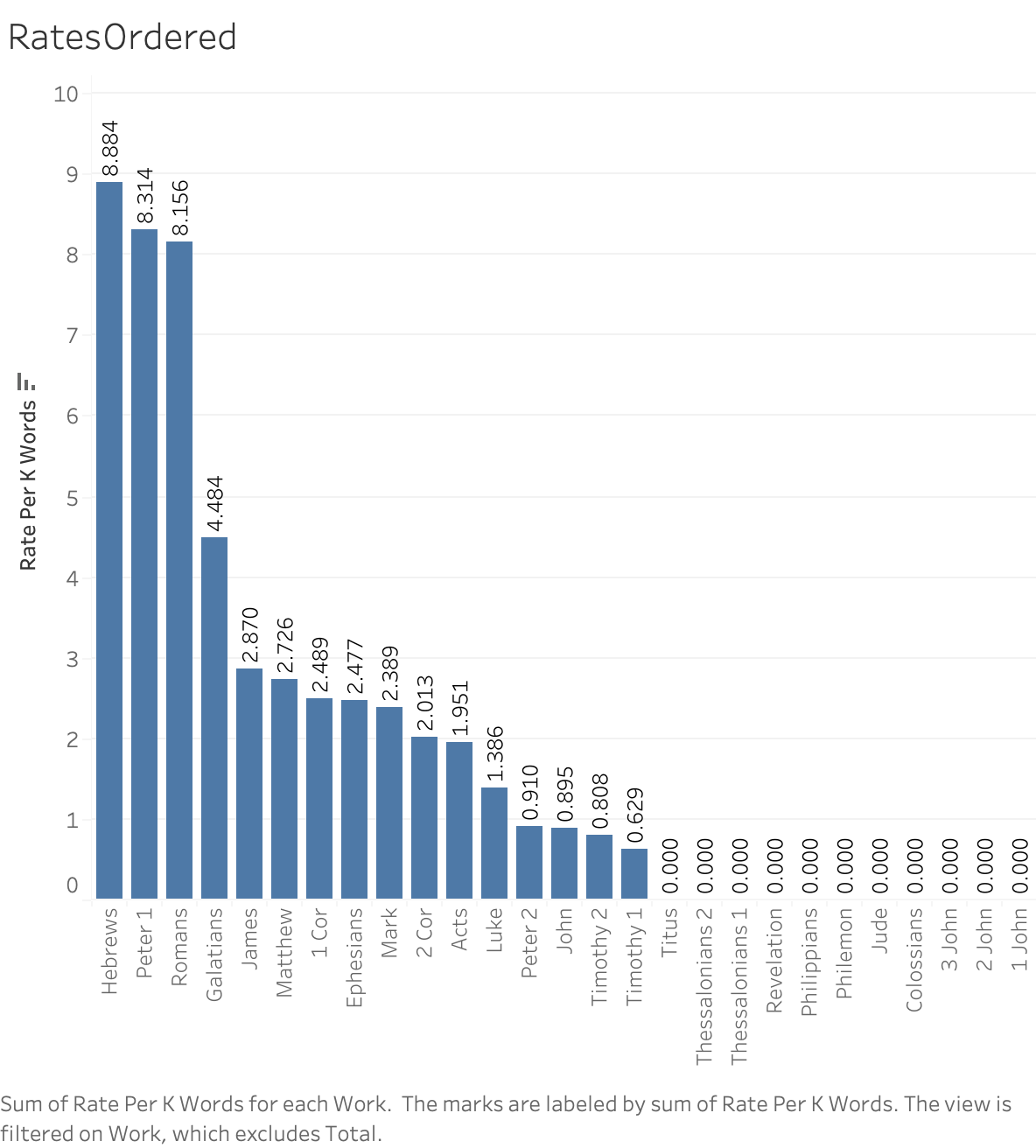

Returning to the data: here are the densities, ordered:

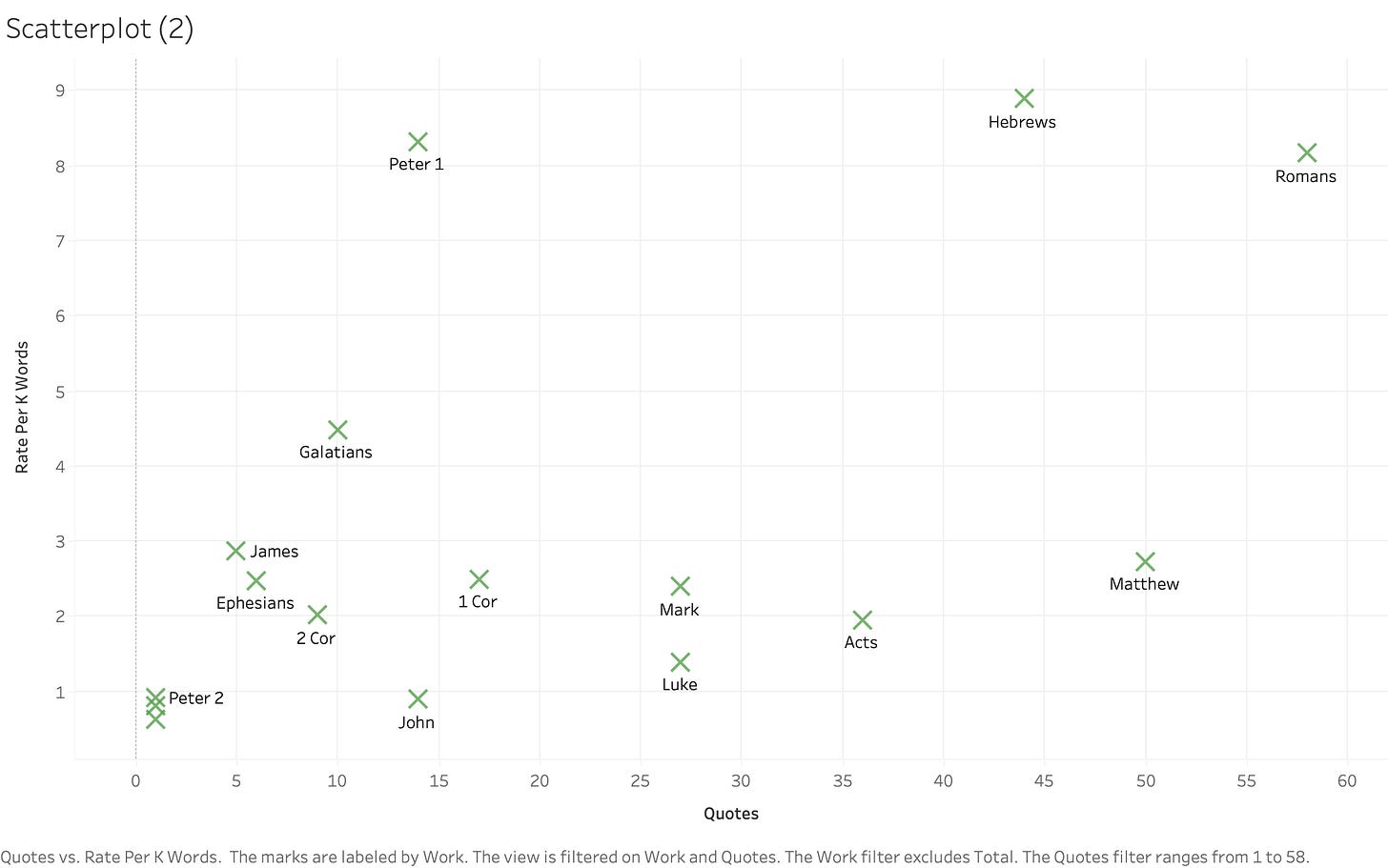

Another aside: about this time in my data visualizations, I did wonder just how much of a role book length mattered. If there’s the whole cluster of 1/2/3 John and Jude that include nothing, but the most quotes belong in the single longest book (Matthew), is it basically the trend that longer books wind up with more quotes? (For a moment I envisioned the writing proceeding like a research project, where the shorter letters were just dashed off but the longer works involved more studious reference to the OT.) Now of course, if it were as simple as that, we would see all densities that were roughly the same one value—but even so, I wanted to bring this idea into greater focus.

Here are the books’ # of quotes alongside their density. So you have Romans and Hebrews that are dense and copious, up there with Matthew, Luke, and Acts, with pretty modest densities whose high counts are mostly driven by their length (they are the 3 longest books in the testament). This plot does sorta suggest that there’s a band of typical frequencies (lining up all the observations between .5 and 3 on the y axis), with just three (and a half) outliers bucking the rule. But there’s clearly a smattering of this data, rather than a solid line.

And, last variation on this particular data, this is a scatterplot of number of quotes against word counts. This should be a straight line if there were one governing density, but instead, it looks more like a blob. Or like a manta ray.

I think I’ve seen jokes on XKCD about finding new constellations in scatterplots.

Ok, enough with that aside.

I mentioned earlier that there are other methodologies. One dude at The Gospel Coalition picked up this Jeopardy! controversy and wrote about it, including some of his own tallies, which distinguish between “citations (that are marked with an introductory signal like ‘as it is written’) and quotations (that are verbatim from an Old Testament passage but lack an introductory signal).” He’s apparently published a full table in a book of his (I don’t own it), but he reproduced the top 10—and, as you guessed it, no combination of citations vs. quotations vs. sums quite equalled my own tallies. But I wanted to see what his looked like.

For the “top 10” which he produced in the article, here they are, per book:

The red dots represent citations, according to the tick marks on the left axis. The blue dots are his “quotations,” measured according to tick marks on the right.

The chart seems dominated by a lot of the familiar players. So, here are the bar graphs side by side, my counts (top) compared to the sum of his 2 categories at bottom:

Apologies for the “missing teeth” in his bar graph just from incomplete data.

I don’t know how I wound up with a good number more in Hebrews than he did. I even started throwing a different counting method of my own (counting my ESV study Bible’s footnotes in Hebrews that specify “cited”), and got far enough to see that I was once again going to outpace his tally.

But regardless, the same general story is told. It’s only at the margins that this becomes an issue.

Then I threw his enumerations into my word-rate-calculation and examined the results. Behold.

There’s more I want to say—about scientific studies in general, and the logic of clue-writing, and the way that apparently Jeopardy! just today finally spoke out on the subject (I haven’t listened to it myself yet but what I’ve heard is not convincing)—but I’ll have to leave these topics for another day.

~

A lot of this has taken place at the level of data—summary statistics and tallying things, not in a numerological way but just assessing at an abstract level the character of these books. But I wanted to at least highlight one of these actual quotations.

That one time that 1 Timothy, with its tiniest (by my enumeration) frequency, quotes the OT, it’s actually rather interesting.

Paul’s instructions to Timothy at that moment (1 Timothy 5:17-18) read “Let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in preaching and teaching. For the Scripture says, ‘You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain,’ and, ‘The laborer deserves his wages.’” (ESV). That’s two quotations. The first one is from Deuteronomy 25:4; the second is actually from Luke 10:7. This is really interesting internal evidence to just how early it was that the New Testament (such of it as existed at the time) was already being considered “Scripture,” i.e. of the same kind of thing as the Old Testament.

~

Incidentally, I much prefer a Final Jeopardy clue from back in 2011, under the category “Ancient Writings”: “In 170 A.D. Melito of Sardis compiled a list of religious works to be included in this, a 2-word term he coined.”

~

The fine print of the methodology

I used my Zondervan edition of the Greek New Testament (2nd Edition) to facilitate my manual tallies of the Old Testament quotes in the New Testament—they bold them, and footnote the references. I tallied each quote for one, even if it was quoting multiple lines in the Old Testament at the same time. So e.g., any quotation of one of the Ten Commandments was a quote of both Exodus and Deuteronomy, but since I was just interested in seeing how dense the NT writers were in referencing the OT, I tallied it for one. I also tallied each separate quote once even if one line in the NT was quoting OT texts that were practically adjacent—so e.g., Hebrews 2:13 counts for 2, as does 1 Peter 2:9. Also note that I decided to tally quotations and measure per 1,000 words—one could also count the words in OT quotations, to see how much of a NT book is OT quotation, rather than looking into how frequently in a given amount of space a NT book referenced the OT. I was marginally more interested in the latter question—also, counting all the individual words would have been far, far more time-intensive.

~

Answer: Brazil has won the most, with 5; Germany/West Germany (hence “8-ish”) has won 4, as has Italy. Argentina, France, and Uruguay have all won a couple (France won it last time); and Spain and England have both won one.