Common Knowledge and Mutual Knowledge

[Trivia: How many of America’s 13 or so laureates of the Nobel Prize in Literature can you name?]

I keep hinting at this significant difference between “common knowledge” and “mutual knowledge,” and today felt like a good day to get around to discussing this.

This distinction comes from game theory, which is the branch of mathematics that studies scenarios where people have information and make choices with an eye towards payoffs. That applies to what we ordinarily call games, like tic-tac-toe and chess, as well as, well, potentially any other situation in life—the “prisoner’s dilemma,” voting, going to war, bribing officials, “chicken,” penalty kicks in soccer, picking a location for a gas station, etc. (My college cross-referenced the class as either a Math or an Economics credit.) The prisoner’s dilemma is probably the most familiar game, but there are plenty of games that aren’t so dour or even antagonistic. There’s an entire collection of “coordination” games that are predicated on multiple parties getting better off together.

Picking a bar to meet up with friends at is a good example of a basic coordination game. You and some other friends could happily hang out at any of a couple different bars; the key is that you’re all on the same page about which one you’re each headed to when you’re free. Social media sites are sort of similar—you might not especially care about Facebook or MySpace, but you’d strongly prefer that there be one social media site you can log on to to interact with all of your friends. You could almost consider language as a coordination game, since the key is whether you and your friends can all talk with each other—except for how, realistically, there’s very little choice in which language we wind up being able to speak.

In a way, participating in the town bank is also a coordination problem. If you keep your money under your mattress, great; if you deposit it at the bank and earn security and interest, that’s also great. But it would suck to be missing out on interest—and it would also suck if, all of a sudden, everyone else in town heard there was a depression and pulled their money out of the bank, and you found yourself with nothing material to your name.

“The money’s not here . . . why, your money’s in Joe’s house, that’s right next to yours—and in the Kennedy house and Mrs. Mecklin’s house . . .”

That’s a slightly different type of coordination problem because, while we might have no real preference which bar we all hang out at, it’s clearly a superior outcome for everyone in town to trust the bank and benefit from its security and interest (and ability to make loans to people) rather than for everyone to be sleeping on lumpy mattresses. So, there’s coordination over a good outcome and a bad outcome, but no one person can ensure the good outcome for themself.

Now, if you’re a person living in that town, you can expect everyone else in that town to be knowledgeable enough to understand the situation as I’ve just laid it out. And there’s probably a bank, so you put your money in. But then one day, the newspapers’ headlines scream about a financial crisis and you notice other people rushing downtown.

As far as your bank is concerned, it’s still better for everyone to trust the institution and leave their money where it is. And if someone pulled you aside and reminded you of that fact—it probably wouldn’t matter much. It would probably not dissuade you from trying to get your money out of the bank while you still could, even knowing that the better coordination is for everyone to leave it where it is, and even knowing that everyone else also does understood that reality.

But if someone stood up in front of you and the whole crowd of people (as happens in It’s a Wonderful Life), and reiterated how much better everyone is to keep putting faith in the bank, people might actually refrain from withdrawing.

What changed? It’s the difference between multiple people knowing the same information (being aware of how trusting banks is good and individual money holding is suboptimal) and a situation where they know it, but also know that everyone else knows it too, and that everyone knows that everyone knows it, and so on and so on. This is the sort of information that emerges when something is said in a conversation or at a public event. If I say to a group of friends that “The cat’s name in Pinocchio is Figaro,” then it’s not just the case that everyone present now knows that fact; it’s also the case that everyone present knows that everyone else heard it and they all know it too, and they know that each other knows it, etc. (This example is largely adapted from this excellent lecture.)

For our coordination games, this kind of communication can change group behavior. Payoffs don’t need to change, threats don’t need to be made, promised interest doesn’t need to be elevated—just the communication can change people’s actions because of the nature of that kind of awareness that everyone is on the same page.

This is one reason why we have group chats. It’s not just so that we don’t have to paste the same message several times over; it’s because it’s powerful, and often necessary, to say things to a group and have that ad infinitum recursion of people knowing that everyone else knows it, and so on.

It’s also perennially relevant in political debates. If some male political figure has been accused by a woman of having sexually harassed her in the early 90’s and, having been spurned, subsequently retaliated in the professional arena to obstruct her career, then it actually matters a lot for the purpose of the public conversation whether the media has so blanketed the world with coverage on the subject that it rises to the level of everyone being aware that everyone else knows about it, too. If so, then Democrats can feel free to still repeat sidelong if not accusatory remarks against Clarence Thomas, regardless of whatever merit the underlying initial allegations had. After all, the allegations have a very public status (that the weaknesses don’t) that means that, even if you raise them to someone who’s entrenched against the idea that they have any merit, you’ve now changed the conversation into one that’s putting Clarence Thomas on trial for sexual misconduct, and what’s remarkable is that it’s your opponent’s awareness of an allegation he finds distasteful and false that has enabled that outcome that he doesn’t like. If, on the other hand, I mention Tara Reade in connection with our current president, I doubt whether most politically engaged people would know whom I’m talking about. It’s hard even to gain traction with a topic like that.

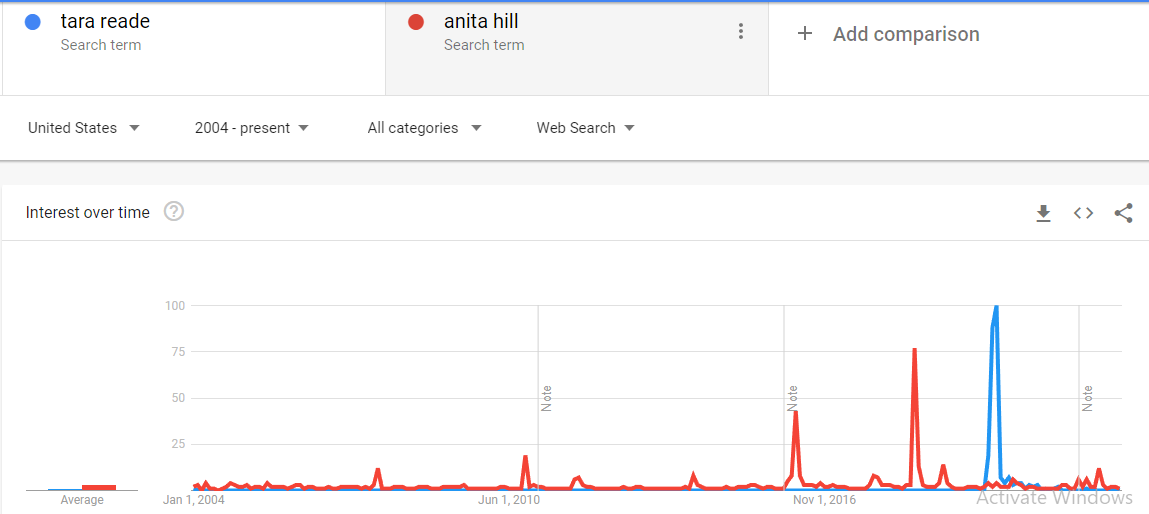

Tara Reade does own Google Trends’ #1 high point over Anita Hill, but the continued relevance of Hill is something to behold.

At this point, you might be expecting me to tell you which of these is “common knowledge” and which is “mutual knowledge.” Generally speaking, “mutual knowledge” is what multiple people both know. “Common knowledge” is what a set of people know, and know that everyone else is aware of it too, and that awareness is known by everyone else, to infinity and beyond. (Note that all mutual knowledge has to be common knowledge too, it turns out.)

There’s a little bit of a caveat. The concept of common knowledge, so termed, comes from a 1969 work by David Lewis, and “mutual knowledge” was distinguished by Stephen Schiffer in a 1972 book. But then again, my game theory textbook, published as late as 2007, feels the need to point out that at least someone (Brandenburger 1992) was going around using the term “mutual knowledge” to mean what is otherwise called “common knowledge.” I’ll try to use that, myself, since that seems to be what the world is homing in on. But it certainly strikes me as ironic that in dialogue about information and communication, game theorists are struggling with their own coordination game.

~

Answer: Sinclair Lewis, Eugene O’Neill, Pearl S. Buck, T.S. Eliot (who had by that time become a UK citizen and renounced his American citizenship), William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Isaac Singer, Joseph Brodsky, Toni Morrison, Bob Dylan, and Louise Gluck. You could also arguably include Czeslaw Milosz (the Polish expat/refugee from communism whom I keep quoting), who was from Poland but at the time of his winning the prize for “with uncompromising clear-sightedness voic[ing] man's exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts” he was a citizen of, and living in, the USA.